Welcome to the second part of my ongoing translation of 牧場物語2 (Bokujō Monogatari Tsū, Harvest Moon 64)’s Variety Channel. Dubbed the “Entertainment Channel” by fans, it was cut from the game’s only English release, and has never been translated until now. If you’re looking for more information on why I’m doing this, as well as how to use the Japanese-learning resources at the end of the article, check out the landing page here. If you’re looking for the first part, click here. Otherwise, let’s check out this week’s shows!

| Japanese | Direct Translation | Localization |

|---|---|---|

| スポーツでポンの時間です。 | It’s time for Pop! via Sports. | *crack* It’s sports time! |

| プロやきゅうワイルドシリーズ 第3せん、カウズ対ホーゼズの しあいが行われました。 | In pro baseball’s Wild Series’ 3rd match, a Cows vs. Horzes match was performed. | The Cows faced off against the Horses in Game 3 of the Wild Series today. |

| マサイせんしゅのホームラン2本を ふくむ4あんだの大かつやくで、 カウズがホーゼズにれんしょう、 ゆうしょうに王手をかけました。 | A Maasai player’s 2 home runs included in his 4 base hits played a very active role, with the Cows’ winning streak over the Horzes locking them in check for the championship. | Batting 4 base hits—2 of which were home runs—the MVP played no small part in continuing the Cows’ winning streak and placing them one game away from a championship sweep. |

Our fourth show is a sports recap. This show always has extra-long sentences, so if you struggle with conjunctions, it’s gonna hammer them into your brain! Aside from that, though, so long as you know the vocabulary, the meaning shouldn’t be too hard to tease out. Let’s take a look at specifics, shall we?

The title’s the first thing that’ll probably catch most peoples’ eye. スポーツでポン (Supōtsu de Pon) follows a pretty common pattern in Japanese titles. Before specifically explaining its meaning, lets look at a couple examples you might be familiar with:

With these in mind, we can see that pon indicates a “pop” sound. With スポーツで preceding it, it indicates that the “pop” sound is being caused by sports. To me, the closest connection is the sound of a bat connecting to a baseball (think of the phrase “pop fly”), but I’ve seen pon used to describe the sound of a tennis racket making contact, as well. There’s no one right answer. Regardless, I think it doesn’t really work to translate it as part of the title, but having a sound effect during the introduction sounds good to me! For an example of a similarly-difficult name to localize, you might be interested in why Psycho de Yoroshiku!! from Live A Live has never been translated correctly.

Moving on, this show has a ton of loanwords! Like sound effects, loanwords are usually indicated by being written katakana as opposed to hiragana or kanji. They’re essentially just foreign words that have become common enough that Japanese people know them despite being, well, foreign. It’s like how native English speakers generally know the terms tortilla, ad hominem, and omelette du fromage even though they’re Spanish, Latin, and French.

Most loanwords in this work are pretty straightforward, but you might have caught on that ホーゼズ (Hōzezu) didn’t seem quite right. It’s closer to “Hoses” or “Horzes” than “Horses”, so I’m given to believe it’s either a mistake or a stylization on the writers’ part. Given that they’re facing the カウズ (Kauzu, Cows) “Horses” certainly seems more appropriate.

At the time this game came out, a cocktail called a Horse’s Neck was pretty well-known. The correct spelling of this drink in Japanese is ホーセズ・ネック (Hōsezu Nekku), but, interestingly, ホーゼズ・ネック (Hōzezu Nekku) is the most common Google result for hōzezu by far (though it still doesn’t get all that many results). All that said, I think hōzezu might have been a common misspelling of “horses” that fell out of fashion before we entered the digital age, and this cocktail is sort of the last surviving reference to it, since it, too, fell out of fashion around the same time.

Lastly, I think we better cover some of the baseball-specific terms. First, the sportscaster uses 本 (hon) as a counter for runs. Just like in English, Japanese has all kinds of specific counters for specific situations, and it’s pretty important to learn all of them if you want to sound natural when speaking. Just like it wouldn’t do to say “4 things were scored,” instead of using “runs”, it also wouldn’t sound right to use the generic つ (tsu) counter in place of hon. You can learn a lot more about this counter from this Tofugu article, if you’re interested.

Another term used is 安打 (anda, safe hits). Just like the English baseball term “hit”, these track when a batter hits the ball such that he and all the other runners successfully advance a base. Also like a “hit”, it only counts when it’s due to the batter’s success hitting, not some sort of failure in the defense’s play. You’re going to learn a lot of specific sports terminology from this show, which will probably have been a gap in your Japanese knowledge! Japan’s crazy about baseball, so consider it a step on the path to fluency!

With all that said and done, I think we’re ready to move on to the next show:

| Japanese | Direct Translation | Localization |

|---|---|---|

| (ふー、一体なんだっていうんだ) | (Sigh, why the heck was that said?) | (Sigh, why’d she say that?) |

| めちゃめちゃになった部屋を見て ため息をつくいちろう。 | Ichirō looks at the room which had been made messy and lets out a sigh. | Ichirō laid in bed and sighed as he looked at his room, now in disarray. |

| 恋人のふみえとのケンカのあとだ。 | It’s the remains of the argument with his girlfriend, Fumie. | The mess was a scar left by the argument with his girlfriend, Fumie. |

| (そんなにわるいことなのか? | (Is it that bad a thing? | (Is it really that bad? |

| 少なくとも、ワンツーでパンチ されるほどのことじゃないぞ!) | At the very least, don’t go to the extent of a one-two punch!) | At the very least, it wasn’t worth the one-two punch!) |

| ベッドにあおむけになり、 いちろうは目をとじた。 | Becoming upward-facing in the bed, Ichirō closed his eyes. | Ichirō rolled onto his back and shut his eyes. |

| つづく | (The story will) continue | To be continued… |

Behold the first episode of 運命の赤い糸 (Unmei no Akai Ito, Red String of Fate). From just the title, it’s clear this is a romance story! We’ll see how Fumie and Ichirō deal with their recent spat, and how their friends deal with them. It’s definitely on the dramatic side, but there’s a comedic element, as well. Not much happens this episode, which is good, because the premise requires a lot of explanation.

The red string of fate gives me a great opportunity to talk about mythology, history, and culture—which I love doing—so I won’t pass it up! If you consume anime and other Japanese fiction, you might have seen a red string connecting two people who are destined to be together. If you consume a LOT of those works, you’re probably familiar with its function as romantic symbolism.

What you may not be as familiar with is its mythological origin. The thread (invisible but still somehow red) comes from 月下老人 (yuèxià lǎorén, lit. “The old man under the moon”), a figure from Taihei Kōki, a collection of Chinese literature from the Song Dynasty.

The story goes that the old man was a figure from the world of the dead who was responsible for assigning two people to be married. He did this by tying a red rope around their ankles, which will never break regardless of how far apart the two are or the circumstances they’re in. Notably, the story uses 縄 (nawa, rope; cord), not 糸 (ito, thread; string), in this oldest iteration of the story. Maybe Kimi no Na wa‘s title and thick red rope bracelet/ribbon is an intentional play on words?

In any event, as the story unfolds, a young man asks if he can marry a specific woman. The old man warns him that she’s already tied to another man, so it won’t go well, and—when pressed—tells the man he’s already tied to someone else, a child. Frustrated, the young man orders his servant to kill the girl, and she’s stabbed between the eyes. As the man ages, he has no success with romance, until he’s introduced to a young woman with a wound between her eyes. He learns the girl survived her injury, and marries her, taking excellent care of her to atone for his past misdeeds.

As you can see from this fairly gruesome origin, while it’s often compared to Cupid’s arrow, the red string is less of a “mind control” story and more of a “soul mates” one. The trope has also evolved due to exposure to not only Japanese culture, but the West, as well. Most notably, the rope-turned-thread now ties around the little fingers of the lovers’ left hands (well, sometimes it’s the man’s thumb).

The reason for the change has to do with the intersection of wedding rings and a practice known as yubikiri. First, the West’s wedding rings became popular as a symbol of romantic intent, so, naturally, Japanese fashion changed when exposed to that. The practice of putting wedding rings on the left-hand ring finger stems from an Ancient Roman belief that that finger was connected directly to the heart by a single vein, so the symbolism is pretty obvious. Putting a bulky rope on your finger doesn’t really work, however, so that’s likely why it was downsized to a thread.

As for yubikiri, its literal meaning is “finger-cutting”. Pretty scary stuff! As a romantic term, it derives its origin from prostitutes of the Edo period (back to Edo already, huh?). To signify sincere romantic intent to a love interest, a prostitute was said to cut off the tip of her left pinky finger to show the permanence of her feelings. Since she could only pull that trick once, it was pretty meaningful!

In truth, this practice might be apocryphal. There’s not many accounts of it, and even reports of fake fingertips in some historical documents. Still, the idea of a person loving someone else so much they’re willing to permanently disfigure themself is very emotionally charged, and has persisted through to the modern day. The romantic weight of the pinky finger persists, as well.

Whew! That was a lot for the “culture” section! It was very necessary to understand the symbolism behind the red string of fate, though, because of how this show progresses. Luckily, the writing is conversational and simple, so I don’t have much in the way of vocabulary/grammar notes. I guess the only thing that might trip you up is misidentifying 一体 [ittai, (what) the heck] as 痛い (itai, pain; ouch) since they’re both used as exclamations. Look out for the glottal stop! If you don’t know what that is, don’t worry; it’ll come up in our next show:

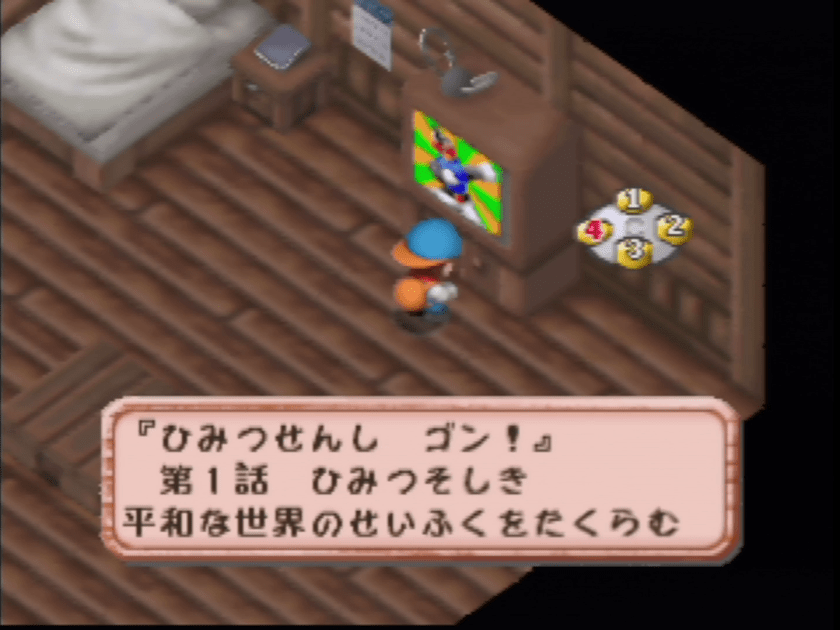

ひみつせんし ゴン!

第1話

ひみつそしき

Secret Soldier: Gon!

Episode 1

Secret Society

| Japanese | Direct Translation | Localization |

|---|---|---|

| 平和な世界のせいふくをたくらむ ひみつそしき “ジョーカー”! | The secret society “Joker” is planning to subjugate the peaceful world! | Looming in the shadows, the terrorist organization Joker plans to take over the world! |

| ボス “グラフ・コンカー”は 手下を使い、ひみつのじっけんを つづけていた。 | The Boss, “Graph Conquer”, was continuing a secret experiment using his henchmen. | Right now, their leader, Graph Conquer, has been conducting secret experiments on his henchmen. |

| パチッ! | Click!! | With a “click”, a switch is flipped |

| ピカッ! | Shine!! | and a dazzling light fills the room |

| ビリビリビリビリビリ~バチィ! | Bzzbzzbzzbzzbzz~bzzt! | as electricity violently courses through the test subject! |

| はげしい音ともにせんこうが走る。 | A violent sound together with a light flash. | As the electricity drains, the violent cacophony stops. |

| ゆらゆらとゆっるけむりの中から 男のかげがあらわれた! | From inside shaking and flickering smoke, the shadow of a man appears! | Billowing smoke fills the room, and the silhouette of a man can be seen! |

| つづく | (The story will) continue | To be continued |

We’ve reached the penultimate show in our set of seven! From this alone, the premise of the story isn’t completely clear, but you can see that it has a darker tone compared to the other shows in both this game and the Bokujō Monogatari series as a whole. Another interesting point is that Secret Soldier: Gon! is 20 episodes long, while every other show finishes on episode 10. Lastly, this is the only show in the game where each individual episode has an actual title.

Speaking of titles, the せんし (senshi) included in this one is a bit interesting. You’re assuredly familiar with some works that use it, but you may not be aware of its precise meaning. Generally speaking, it refers to anyone who makes fighting a career or lifestyle. The most-readily-conjured image is that of trade warriors such as samurai, knights, and gladiators, but the use can be played with a little.

At this point in time, it won’t be clear even to native readers exactly where this story is going, or even the precise meaning of the title. When it’s revealed in the show, I’ll explain the full meaning of ゴン (gon), but, for right now, I think a reasonable assumption on the reader’s part is that it’s a sound effect. Gon generally evokes a powerful impact, like that of a heavy punch or kick. The idea is that something’s been hit hard enough for the hit to make a “gong!” sound, as seen below:

To be honest, this is probably the intended initial reading, as ゴン is written in katakana, which often indicates a sound effect. Part of the “joke” here is that Secret Soldier: Gon! uses an incredible amount of onomatopoeia, much like Live A Live‘s Caveman chapter. For a non-native speaker, Japanese onomatopoeia can look like nonsense without a good example of the sound they’re thinking of. I can’t hunt down videos for every single one, unfortunately!

That being the case, I recommend bookmarking The JADED Network’s searchable onomatopoeia database. Not only can you search for whatever you’re looking for, but the entries are sometimes accompanied by examples from manga. The site hasn’t really been updated since 2013, so some examples might be a bit old-fashioned, but there doesn’t really exist a better centralized resource on the topic, as far as I’m aware.

Still, I’ll try to give a quick overview of the onomatopoeia in each episode. First, we have pachi, pika, and biri biri bachi. Pachi (パチ) evokes a click, clap, or snapping sound. You’ll often see it for clapping as pachi pachi pachi, but in this case, it’s more likely to be evoking the press of a button or the flip of a switch. As for pika (ピカ), you’re assuredly familiar with Pikachu, the electric mouse Pokémon. The first half of its name comes from this onomatopoeia, which conveys a flash or sparkle.

Lastly, biri biri bachi (ビリビリバチ) is really two sound effects. First, is a repeated biri, which conveys a rip, shock, vibration, or pricking. Repeated over and over as it is in the show, it’s almost unmistakably the sound of electricity coursing through something. Next we have bachi, which can be the sound of crackling electricity. In this particular context, it conveys that the electricity has stopped, though the small i (ィ) at the end gives the impression of it draining out slowly, rather than with the suddenness bachi often implies.

Speaking of sudden stops, a quick note on the tiny ッ kana (known as 促音, sokuon) you see at the end of some sound effects: in linguistic terms, this indicates a brief pause known as a glottal stop, and is also referred to as the geminate consonant. In a lot of Japanese words, it’s accompanied by a doubled consonant sound (such as in ケッコン, kekkon), but at the end of sound effects, it indicates a sudden or impactful end to the sound. Keep an eye out for it!

Lastly, we have ゆらゆら (yurayura), the onomatopoeia for swaying, shaking or flickering. Most commonly, I see it used to describe the movement of a flame. Here, it’s used to describe smoke, so I’d say it’s an almost perfect match for the English “drifting”.

If you’re not very familiar with onomatopoeia, this detailed explanation might seem confusing or unnecessary, but the fact of the matter is, proper understanding and implementation of Japanese onomatopoeia is essential. Sound effects are used not only in a dramatic setting, but also conversationally, as nouns, adverbs, and adjectives. If you have a ちゃらんぽらん (charanporan, blithe; apathetic) attitude towards onomatopoeia, even if you study そろそろ (sorosoro, with care and patience), your will never speak Japanese ペラペラに (peraperani, fluently). Luckily, as we go on with this show, you’ll learn plenty of sound effects and how to use them!

With Secret Soldier: Gon!‘s first episode out of the way, let’s move on to the final show!

少女たんてい

いちごちゃん

第1話

Ichigo,

Girl Detective

Episode 1

| Japanese | Direct Translation | Japanese |

|---|---|---|

| いちごちゃんは、なぞときの 大好きな小学1年生。 | Ichigo-chan is a first-year elementary school student who loves unraveling mysteries. | Ichigo is a first-grader who loves solving mysteries. |

| いちごちゃんが学校に行くと、 見たことのないおじさんが 校もんの前をうろついています。 | When Ichigo-chan goes to school, a middle-aged man she’s never seen before is hanging around the school gate. | Today, she’s spotted a man she’s never seen before loitering outside the entrance to her school. |

| (まぁ、あやしいわ!) | (My, kinda suspicious!) | (Oh, he’s a li’l suspicious!) |

| いちごちゃんのひとみが キラリと光ります。 | Ichigo-chan’s eyes sparkle and shine. | Sensing a new mystery to solve, her eyes sparkle. |

| つづく | (The story will) continue | To be continued |

Simple title this time around! As you can probably guess, this is a “kid detective” show. It pays homage to a particular series written by Edogawa Ranpo that I’ll discuss when the time comes, but if you’re familiar with Goshō Aoyama’s Detective Conan or Donald Sobol’s Encyclopedia Brown, you’ve got your expectations in the right place. This is probably the simplest of all the stories we’ve seen so far, and the notes I want to give on Edogawa’s story will spoil a later plot beat, so perhaps the best course of action is to just talk about the many ways this story tries to endear Ichigo to us right off the bat.

You probably know ちゃん (chan) as an honorific suffix attached to the end of peoples’ names, but maybe you don’t know its exact meaning. That’s understandable, since even Japanese resources on complicated linguistic topics like honorifics are generally described with vague terms that only give the reader an “impression”, not a strict ruleset, and Westerners are usually a little uncomfortable explaining them.

Essentially, chan is used to add a little bit of politeness or respect when addressing someone. I would say it’s not actually a noticeable level of politeness in the transition to English, but the lack of a chan would be noticeably impolite. Italics. Chan is typically reserved for very young children (6 years old or younger) regardless of gender, girls of school age, pets, close friends, and family, and you could say it recognizes the “personhood” (even of pets) of whoever’s being addressed with it.

It’s easier to understand when contrasted with さん (san), another honorific which adds respect while also acknowledging a level of “distance” between the speaker and the subject. Chan is best-placed when you want to show that you don’t want to disrespect someone, but also that you feel close enough to them that you can “let your hair down”. A rule of thumb I’ve heard is that if it would be appropriate to call someone “cute” to their face, it’s also appropriate to use chan. So you shouldn’t use it for coworkers unless you’re pretty good friends!

Ordinarily, one wouldn’t use chan in the title of a work purposelessly. For example, 涼宮ハルヒの憂鬱 (Suzumiya Haruhi no Yūutsu, The Melancholy of Haruhi Suzumiya) doesn’t append a chan to its eponymous lead’s name in the title. In this case, it’s one of many things designed to give Ichigo a certain image. She’s so cute, young, and feminine that she is objectively chan material, and you should feel the level of closeness and adoration necessary to call her that.

The image-building doesn’t stop there. Ichigo‘s name (いちご) means strawberry, a fruit associated around the world with sweetness, innocence, and femininity. In Japan in particular, it’s associated with cuteness and goofiness, driving the point home even harder. She even dresses like a strawberry in her TV portrait! Lastly, what little of Ichigo’s speech (well, thoughts) we see is also pretty feminine, ending her line with a strongly emotive わ (wa). The まぁ (maa) she starts her thought with has a feminine tone as well, translating to something like “oh my”.

And that wraps up week 1 of the Variety Channel translation. I hope you found it interesting! As will soon become usual, I’ve updated the Anki deck and the vocabulary spreadsheet in advance of this article going live, so if you’re using them to study, you can continue on unabated. Expect the third entry to come out soon (and hopefully be a bit shorter). If you’d like to know about that as soon as it happens, you can follow me on Twitter!

I’ll link the next part here when it goes live, but for now, feel free to head back to the landing page for more info on this project, or to check out one of the other articles on the site. Matthew just uploaded a great 2-part breakdown of the confusing Japanese wordplay in Yakuza 0‘s pager codes, which you can find here and here. Or, for something a little lighter, maybe you’d be interested in how Dark Souls isn’t supposed to lie to the player about what the Tiny Being’s Ring does.